Spoiler or Scapegoat?

How Democrats took the wrong lessons from 2000, never looked back, and are still paying the price.

Conventional wisdom is stubborn. When information conflicts with our prior assumptions, we tend to reject it out of hand. Even when experts show us charts and data and give examples, some ideas just make us shake our heads. Economist Mark Blyth, author of Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea, has described giving fact-packed testimony about the federal deficit to dismissive members of Congress who refused to consider it on its face, and were even less likely to ponder or grapple with it over time.

Something similar occurs when Ralph Nader is mentioned. Of the people who know his name, most have an opinion of his role in the 2000 U.S. presidential election. Many support the “spoiler” theory, saying that Al Gore would have bested George W. Bush had Nader not run. Many Democrats consider this assumption to be self-evident and long-settled at this point. Suggesting otherwise is fightin’ words. Yet the facts support a much different conclusion that casts the Democratic party in a harsher light. In this version, Democrats are betrayers of their stated ideals, beholden to big-dollar donations, and pitted against the working class that drove their heyday.

What Nader Voters Actually Said

Dems’ “Ralph Nader was a spoiler” narrative ignores what his voters actually said, and presumes that they would have voted for Gore had Nader not run. This is a zero-sum approach to the electorate. It assumes that people either vote or don’t, with very little change in the percentage of the population that do either over time. It erases the voices of those who feel disenfranchised by the duopoly.

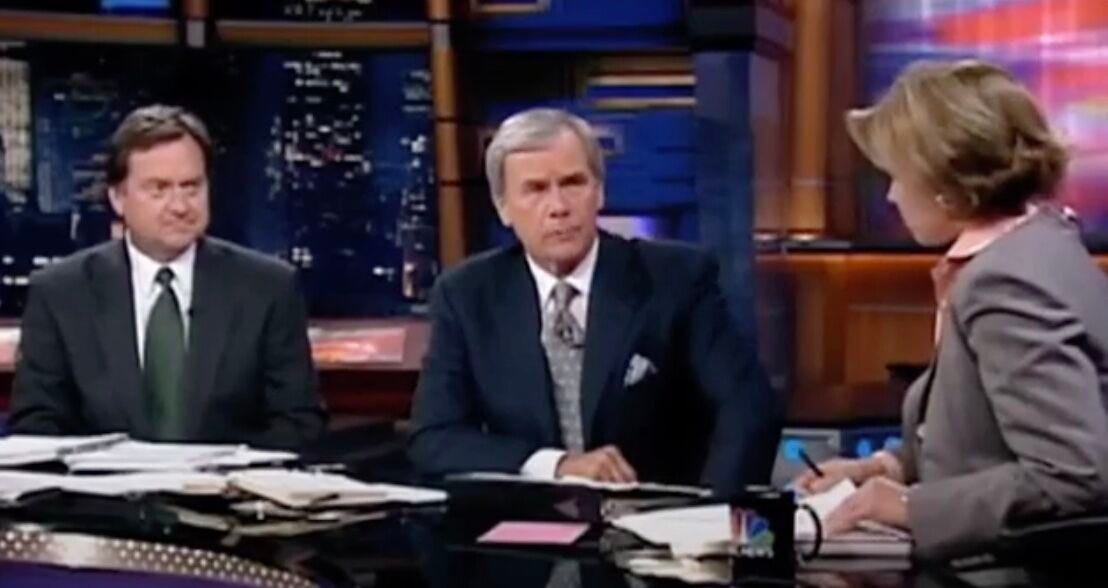

The NBC News team of Tom Brokaw, Katie Couric, and Tim Russert discussed the situation in front of the whole nation on election night 2000. Their exchange, as shown in the 2006 documentary An Unreasonable Man, lasts less than a minute. Brokaw suggests and Couric confirms that Nader voters wouldn’t have voted for either Bush or Gore. Russert notes immediately that Dems would be unlikely to accept that explanation, and would probably just accuse Nader of being a spoiler.

They were all right.

What Democrats Learned: Sue & Shame

The 2000 election traumatized Democrats. In response, they could have looked honestly at their party platform and messaging. They could have listened to the electorate. They could have adopted some of the other parties’ platform planks, which was how the duopoly had neutralized previous threats.

They did none of those things. Instead, they chose to attack the very idea of third parties, and Nader in particular. Since 2000, the Democratic party has used the courts to ensure it only has to deal with the GOP. Republicans got the message, too, and both halves of the duopoly now sue other parties regularly instead of (e.g.) adopting their ideas. Voters who reject the lesser of two evils are shamed outright: “But Republicans!”

The ugly truth is that voters weren’t buying what Gore was selling. They weren’t that thrilled with Bush, either. But pinning 2000 on Nader kept Democrats from asking themselves the tough questions that would have prevented Trump. Like “What would get the 100 million non-voters to become loyal Democrats?”

The thing is, the premise of Nader’s presidential run was and is correct: There are only a handful of issues that separate the duopoly, and both serve corporate donors more than they serve the mass of Americans. That’s proved truer over time.

Democrats have betrayed their stated values for more than a generation. Bill Clinton ran as a populist! Then, as Bob Woodward noted in The Agenda, he turned right around and brought in “the experts”— Wall Streeters who pushed bond trader interests over economic policies that would have helped American people as a whole. Is it any wonder that twenty-plus years after Nader’s 2000 run, demand for a viable new political party is higher than ever?

Still Paying the Price

Ralph Nader isn’t about to stop speaking truth to power. In a recent appearance on the Bad Faith podcast, he scorned the current Democratic party as an arrogant bureaucracy that takes constituencies like labor unions for granted. Don’t worry, he torched Republicans too. In the process, he showed how Democrats are still paying the price for 2000.

Of possible interest: I ran Ralph Nader’s campaigns. A political revolution is vital—and much harder than you think.

Thank you!